Key Takeaways

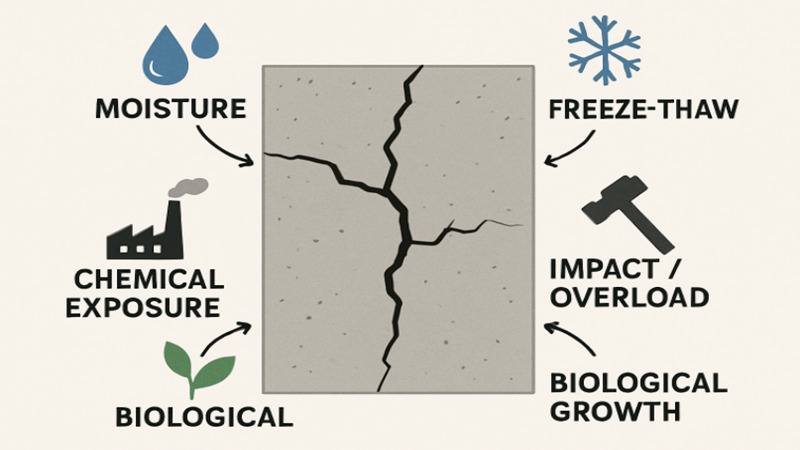

- Corrosion, environmental factors, improper practices, and overload contribute significantly to concrete damage.

- Preventive measures, such as proper material selection, curing, and regular maintenance, are essential for ensuring concrete longevity.

- Addressing sources of damage early, including seeking professional concrete cancer repair, can minimize structural deterioration and repair costs.

Concrete plays a critical role in the safety and stability of modern construction, trusted for its high strength and rugged durability. Still, underlying issues can severely affect its integrity, sometimes going unnoticed until significant damage occurs. Learning about the major contributors to concrete failure empowers owners, builders, and managers to invest in routine inspections and solutions, such as concrete cancer repair NSW, to prolong the life of concrete structures.

Swift identification and timely intervention are crucial, as minor defects can quickly escalate into significant issues. Everyday exposures—ranging from environmental factors to improper usage—can compromise even the best-laid concrete. By applying targeted prevention strategies from the outset and paying attention to climate, chemical risks, and load capacity, the durability of building materials is enhanced for a longer period.

Unfortunately, overlooking any warning signs can have significant financial and safety implications and may even necessitate complete structural redevelopment. Homeowners, business operators, and facility managers should familiarize themselves with the most common threats so they can act quickly when concrete damage appears.

Corrosion of Steel Reinforcement

Concrete reinforced with steel bars (rebar) gains enhanced tensile strength; however, this synergy is susceptible to failure when the rebar corrodes. Water and chlorides—common in marine environments or from deicing salts—lead to rust formation. As corrosion progresses, the expanding rust exerts intense internal forces, causing the surrounding concrete to crack and eventually break away—a process known as spalling. To counter this, concrete cover thickness should exceed minimum standards, corrosion-resistant steel can be selected, and advanced sealers can limit moisture penetration.

Freeze-Thaw Cycles

Regions that experience harsh winters face unique challenges from freeze-thaw cycles. Water seeps into surface pores of concrete; when temperatures plunge, the water freezes, expanding in volume and generating pressure that causes micro-cracks and surface scaling. The use of air-entrained concrete, which incorporates microscopic air pockets, allows space for water to expand safely, thus preserving the surface integrity even through repeated seasonal cycling.

Chemical Exposure

Concrete structures exposed to industrial environments, waste treatment areas, or locations where deicing chemicals are frequently used face another threat—chemical attack. Acids, sulfates, and certain alkali react with the binder and aggregates in concrete, compromising their bond and leading to softening, pitting, and eventual disintegration. Protective coatings, chemical-resistant mixtures, and regular monitoring in high-risk zones are proven methods to withstand aggressive chemical exposure.

Alkali-Silica Reaction (ASR)

Sometimes called “concrete cancer,” ASR is the reaction between alkalis in cement and reactive silica within aggregates, producing a gel that expands as it absorbs water. This internal growth generates pressure, forming extensive cracking often characterized by a map-like pattern. Engineers can curb this by using non-reactive or low-alkali materials and incorporating pozzolanic additives, which bind excess alkalis before damage can occur.

Improper Curing

Optimum strength in concrete isn’t assured immediately after placement—it develops over time, provided curing conditions support hydration. Without proper curing, dehydration can induce surface cracks and compromise durability. Methods such as frequent moisture application, the use of curing blankets, or specialized curing compounds ensure adequate strength and extend the service life of the structure.

Overloading and Impact

Concrete is designed with specific load capacities in mind. Exceeding these—by parking heavy machinery, stacking excessive loads, or accidental impacts—can induce stress well beyond its design parameters, resulting in visible cracks and potential collapse. It is vital to adhere to specified design loads and use additional reinforcement for structures exposed to heavy activity.

Erosion and Abrasion

Surfaces exposed to constant movement of water, foot or vehicle traffic, or airborne particles suffer gradual thinning and surface wear. In critical facilities such as hydroelectric dams, walkways, and industrial floors, surface treatments like silicate-based hardeners and high-strength mixes create a resilient barrier. Selecting finishes tailored to a site’s environmental exposure can dramatically reduce wear rates.

Biological Growth

Bacteria, fungi, and algae can colonize concrete, especially when drainage is poor or the area remains damp. These organisms excrete acids as metabolic by-products, which deteriorate the otherwise robust matrix of the concrete. Timely cleaning, biocidal treatments, and promoting dryness through adequate sloping and drainage eliminate most biological threats before they become problematic.

Prevention Strategies

Prevention is the most effective strategy for concrete health. Regular inspections, prompt repairs, protective coatings in susceptible areas, and the use of high-quality construction materials collectively offer comprehensive protection. For structures showing early signs of deterioration, promptly seeking specialized assessment can make a significant difference in their long-term stability.

Final Thoughts

Concrete is a cornerstone of modern construction, valued for its strength, durability, and versatility. However, its longevity is not guaranteed without vigilance—environmental exposure, improper handling, and material reactions can all compromise structural integrity over time. Proactive measures, including routine inspections, timely maintenance, and professional interventions like concrete cancer repair, are essential to prevent minor issues from escalating into major failures. By understanding the common causes of damage and implementing targeted prevention strategies, property owners, engineers, and facility managers can safeguard concrete structures, enhance safety, and extend service life for decades to come.